Scott Olson

Introduction

Based on free cash flow (“FCF”) prospects, Boeing (NYSE:BA) looked like a reasonable investment until the fatal crash of a 737 MAX in October 2018 followed by another fatal 737 MAX crash in March 2019. Then came the Covid pandemic in early 2020. Boeing took on debt during the pandemic, and interest rates went up dramatically afterwards. The grounding of the 737 MAX, the Covid pandemic and an increased debt load with rising interest rates have severely changed the outlook for Boeing. The stock has come down significantly, but future FCF expectations are down as well. My thesis is that Boeing shows that investing can be very difficult.

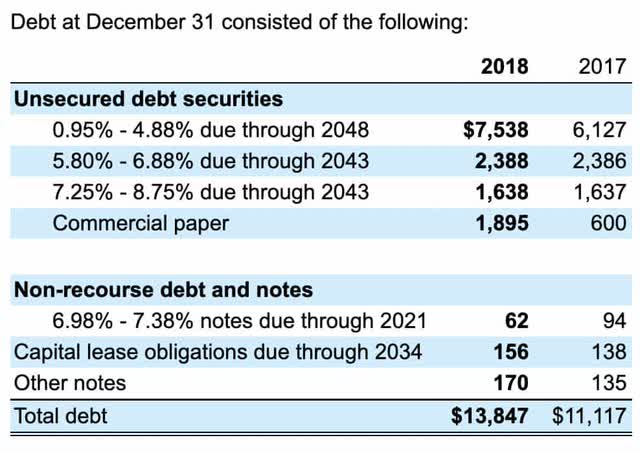

The 3Q22 10-Q shows that the main revenue drivers are commercial airplanes (“BCA”), defense, space & security (“BDS”) and global services (“BGS”):

Boeing revenue segments (3Q22 10-Q)

Before The Fatal 737 MAX Crashes

In the 3Q18 call, former CEO Dennis Muilenburg was optimistic about Boeing’s future. Free cash flow (“FCF”) had climbed from $6.1 billion in 2013 up to $11.6 billion in 2017, and he knew that it would be even higher in 2018. He noted that passenger traffic growth tends to significantly outpace global GDP and he revealed that less than 20% of the world’s population has yet to take a flight.

It seemed reasonable during this time of low interest rates for investors to use a small discount rate on Boeing’s future cash flows in order to value the business at a high FCF multiple.

Fatal 737 MAX Crashes: Lion Air Flight 610 And Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302

The fatal crash of Lion Air Flight 610 in October 2018 was a terrible tragedy. At the time, many headlines focused on the questionable safety record of Lion Air as opposed to the safety of the 737 MAX. However, the fatal crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 less than 5 months later in March 2019 made the world realize that these disasters were related, and the 737 MAX was unsafe at the time. Eventually it was determined that one of the main safety problems with the MAX was the MCAS system, and Boeing has since made adjustments. However, the 737 MAX was grounded for a long period of time. Boeing’s judgment has been questioned and their reputation has been damaged.

Flying Blind: The 737 MAX Tragedy and the Fall of Boeing by Peter Robison is a detailed book that says a number of disturbing things about the 737 program in general and the MAX in particular. Robinson notes that the 737 is the only large commercial aircraft without an electronic checklist. He reveals that 737 pilots are more vulnerable than Airbus A320 pilots and Boeing 787 pilots. He says the number of Airbus A320 and Boeing 737 planes in service in 2018 was similar, but there were just 4 accidents that year involving the A320 and 18 involving the 737. The book also notes the difference in hull-loss accidents between the 737 and other aircraft:

By 2019, Airbus estimated the ten-year moving average of hull-loss accidents for so-called “fourth generation” fly-by-wire aircraft (also including later Boeing planes like the 777 and 787) was one for every twenty-five million flights. The rate for third-generation planes like the 737 was five times higher, about one in every five million.

[ Flying Blind Kindle Location: 650]

Incentives matter. The Flying Blind book states that Boeing promised Southwest Airlines (LUV) $1 million per airplane if the 737 MAX required simulator training. Southwest had ordered 246 of them by 2019, so this was a substantial consideration. Boeing’s management told the flight controls team that they were not allowed to make changes that would require simulator training for pilots. Flying Blind makes the implication that this economic incentive outweighed safety considerations. Simulation is now required anyhow but Flying Blind implies that it shouldn’t have taken 2 fatal crashes for this to happen.

In summary, Flying Blind makes the case that the MAX program was devastating for Boeing:

Meant to cost $2.5 billion – a simple derivative of a model updated a dozen times since the 1960s – the MAX easily exceeded the $20 billion Boeing might have spent on an all-new program. The direct cost was $21 billion, including compensation to customers, aircraft storage, pilot training, and settlements to the families. Through the end of 2020, more than six hundred MAX orders had been canceled, a loss of another $33 billion at typical selling prices.

[ Flying Blind Kindle Location: 4,211]

Covid Pandemic

The Covid pandemic hurt both Boeing and Airbus, but it only caused Airbus to have one negative FCF year – 2020. Flying Blind reveals that Airbus delivered 566 planes in 2020 while Boeing only delivered 157, so it wasn’t just the Covid pandemic alone that hurt Boeing in 2020; it was the combination of the 737 MAX problems and the pandemic.

In the 3Q20 call, CEO Dave Calhoun explained that Boeing filters the air on the plane, which helps prevent Covid from spreading the way it would in unfiltered environments. He talked about the fact that HEPA filters trap 99.9% of particles, and he said airplane air is exchanged a minimum of 20 to 30 times per hour.

The filtering system makes some travelers feel safer during the journey, but people make different travel decisions these days. Some forms of business travel may never get back to the pre-Covid levels.

Increased Debt With Higher Interest Rates

Back in 2018, the future for Boeing looked excellent in many respects. FCF reached its apotheosis of $13.6 billion and the 10-K income statement showed an interest expense line of just $475 million relative to the interest expense line of $2,682 million that we saw in the 2021 10-K. Back in 2018, the net debt load was reasonable, such that the enterprise value was only about $5.4 billion more than the market cap:

$10,657 million long-term debt

$3,190 million short-term debt

$71 million noncontrolling interests

$(7,637) million cash and equivalents

$(927) million short-term investments

—————————————————-

$5,354 million

Substantial debt was added during the Covid pandemic, such that the 3Q22 enterprise value is $43 billion higher than the market cap:

$51,788 million long-term debt

$5,431 million short-term debt

$64 million noncontrolling interests

$(13,494) million cash and equivalents

$(763) million short-term investments

—————————————————-

$43,026 million

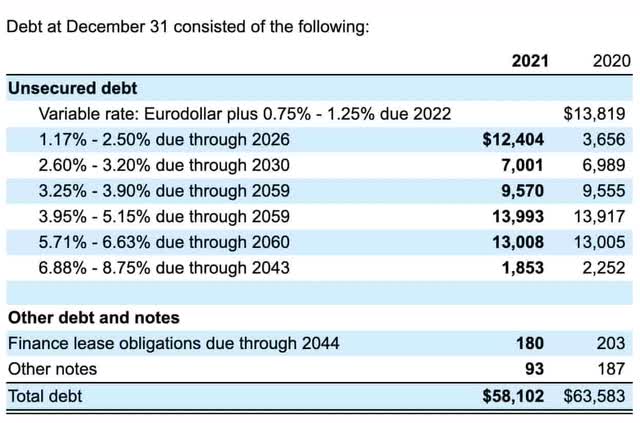

Looking at the 2018 10-K, unsecured debt with a rate of 5.8% or higher was only $4,026 million:

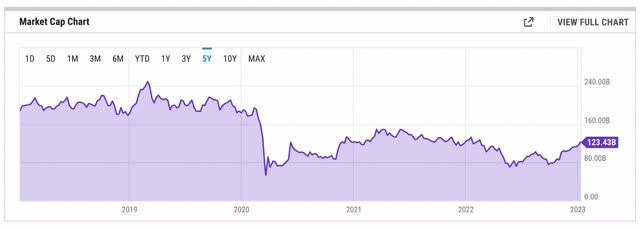

The 2021 10-K tells a different story. Unsecured debt with a rate of 5.71% or more was $14,861 million:

Valuation

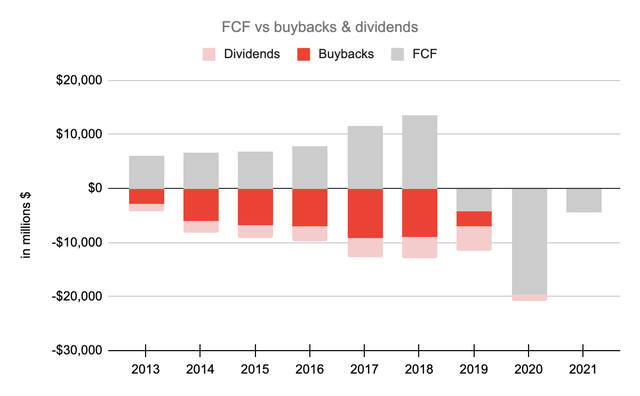

Boeing’s valuation is equal to the present value of the amount of cash that can be pulled out from now until judgment day. Now that interest rates are higher, investors discount future cash more heavily than they did in lower interest rate environments. Buybacks and dividends have been 2 of the main ways that cash has been pulled out over the last 9 years. Ostensibly, Boeing returned $43.4 billion to shareholders in the form of buybacks, but some of this went to offset stock based compensation (“SBC”). The 2021 cash flow statement shows that the share-based plans expense line was $250 million in 2020, but this jumped up to $833 in 2021. $22 billion was returned to shareholders in the form of dividends from 2013 to 2021:

Boeing FCF (Author’s spreadsheet)

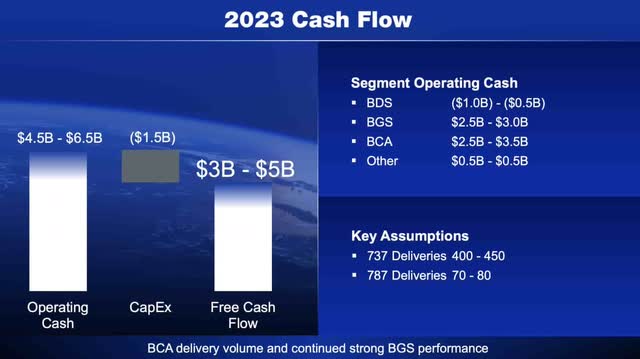

The declining FCF figures above from 2018 to 2020 are a direct result of revenue issues. Per the 2021 annual report, revenue fell from $101.1 billion in 2018 down to $76.6 billion in 2019 and down again to $58.2 billion in 2020. The 2022 10-K isn’t out yet, but the 3Q22 10-Q shows 9M22 FCF of negative $841 million. The November 2022 Investor Conference presentation shows that 4Q22 is expected to be about $2.5 billion, such that the full year FCF for 2022 should be around $1.5 to $2 billion.

The November 2022 Investor Conference presentation goes on to show 2023 FCF should be $3 to $5 billion:

2023 cash flow (November 2022 Investor Conference presentation)

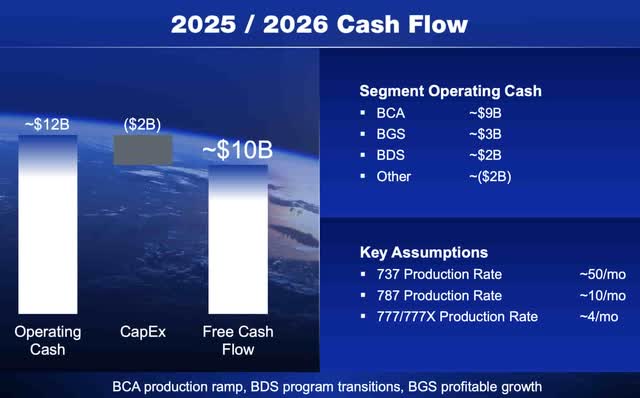

Looking years down the road, the November 2022 Investor Conference presentation shows that the FCF objective for 2025/2026 is about $10 billion:

2025 cash flow (November 2022 Investor Conference presentation)

Underlying that assumption, of $10 billion, is a top line revenue figure of $100 billion and an operating margin of about 10%.

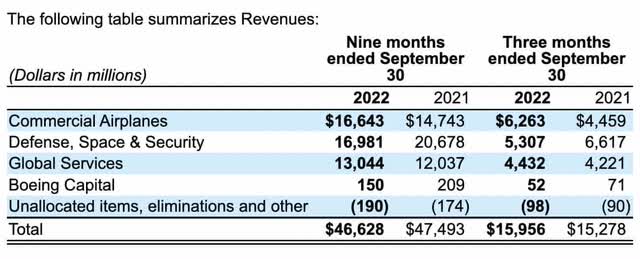

The 3Q22 10-Q shows 595,983,192 shares outstanding as of October 19th. Multiplying this by the January 9th share price of $208.57 gives us a market cap of $124.3 billion. YCharts shows that the market cap has pretty much dropped in half from the level of $246 billion in February 2019:

Forward-looking investors should keep an eye out for the 2022 annual report and the progress with FCF. If Boeing can do what they say and get back to the $10 billion FCF range by 2025 then a considerable valuation is warranted. I don’t think the market cap should be as high as the $246 billion level from February 2019 because things were different at that time. We didn’t know the extent of the 737 MAX issues, the Covid pandemic hadn’t hit, and we were coming off a year where FCF had grown to $13.6 billion. There was less debt on the balance sheet back then and the interest expense was smaller. Interest rates were much lower, such that the discount rate for future cash flows was lower. These and other considerations mean that Boeing’s market cap should not be back to the $246 billion level from February 2019 anytime soon, but if management does well, then the market cap could climb up some from today’s levels.

Source link