The mid-term elections in the US brought a sort of victory for President Biden and Democrats, including the retention of a slim majority in the Senate and suffering only a marginal majority of Republicans in the House of Representatives. Avoided was an expected much bigger electoral victory by Republicans and a clear majority in both houses of Congress. The net result for federal higher education policy is relative stability, although with some important caveats including debates on raising the debt level of the federal government.

A reminder that in the US there is no ministry of education as there is in almost all other nations. Federal policy is largely limited to financial aid in the form of grants and loans to individual students and funding by multiple agencies for academic research. There is a lesser but important role for the approval of independent accrediting agencies and monitoring for violations of civil rights by the US Department of Education.

Most funding and regulatory power lies with state government and their elected lawmakers.

Hence, much of the battles and debates over higher education are at the state level, and here we see a significant difference in the political environment between “blue” (Democratic majority) and “red” (Republican majority) states.

Debates at the Federal Level

This does not mean that national political leaders do not use their position, rhetoric and sometimes vitriol to blame universities and colleges for an array of ills – including high tuition prices and alarming student debt levels incurred more significantly at private and for-profit institutions (a delineation with mostly affordable public universities lost in the national discourse).

Through it all, and as noted, Biden’s higher education agenda remains relatively intact as we move into 2023.

This includes a successful marginal increase in Pell Grants – the primary federal loan program for lower income students. Under his administration, the federal government also allocated substantial COVID relief funds to help universities temporarily transition to more online courses and to cope with losses in tuition revenue due to falling enrollments in many states.

Biden made campaign promises to make community colleges free – a vast network of primarily two-year colleges offering vocational and adult programs, and courses that can lead to transfers to four-year institutions. He also planned to cancel student debt for a large portion of former students, whether they graduated or not.

But those two unrealistic promises morphed over the last year or so. The free community college bid was, in part, Biden’s effort during the 2020 Democratic Presidential Primary to provide a version of competitors’, like Bernie Sanders, proposals for free public university and college, with no regard to a student’s individual or family income. As in other parts of the world, free higher education is popular, even if it is largely an incomplete thought regarding how to pay for it.

The free community colleges plot (virtually all of which are public, local based and largely funded institutions) fell with the failure of a previously $3 trillion and expansive “Build Back Better” proposal by Biden and liberal democrats.

Later, Biden, using his powers as an adept moderate and compromiser and with slim majorities in the House and Senate, got a smaller funding package passed that focused on rebuilding America’s eroding infrastructure. The free community college scheme was dropped. The earlier campaign proposal lacked specificity as to how it would implement its potential progressive impact.

Existing fees are very low in these local institutions and most low-income students already have access to Pell Grants and other forms of financial aid that make it tuition free or nearly so for the most-needy; the bigger problem is that many students don’t know about the various federal and state financial aid programs or how to apply for aid.

Student Debt

Similarly, Biden offered a more moderate proposal for relieving, if not ending, student debt then many of his Democratic rivals in the presidential election.

Instead of a blanket debt relief promise for all no matter their income, he and his policy advisors imagined a more-narrow program for those who took out federal loans: debt relief of up to $10K per former student, and an additional $10K for those who had a Pell Grant but also took on additional federal loans.

About half of all past students in the US took out a student loan. Of those that did, 32.2% owe $10,000 or less in federal debt; 74.2% owe $40,000 or less – not counting those who took out debt at the post-graduate level to become lawyers, doctors and other generally high-income professions.

The Biden plan is also income dependent, offering debt relief for federal loans (not for private bank loans) to individuals making less than $125K, or up to $250K for those jointly filing their tax return with their spouse or legal partner. In the midst of the COVID pandemic, Biden had also previously suspended all federal loan repayments – part of the larger effort to mitigate the feared economic impact of the pandemic.

Biden’s debt relief scheme applies to those who attended a tertiary education institution before 2020. Some 40 million Americans would be eligible with a cost of approximately $400 billion over thirty-years.

White House officials say the debt relief program is for lower and middle-income families. How a couple making $250K is middle-income is hard to fathom when the median household income in the US is just over $70K.

Most scholars and researchers who study financial aid have criticized the Biden plan as too generous and costly, and not targeted enough toward lower income former students. Conservatives also say the same, leading to a lawsuit that challenges the authority of the president to offer loan forgiveness of this scale without legislative approval.

It is important to note that a good portion of those who would be for eligible for debt relief currently have sufficient earnings to pay their student debt; the federal spending would also ignore the many who have already diligently paid their loans. And then there is the inequality of providing this large tax-funded dole to those who willingly chose to enroll in a higher education institution and take on debt, a high percentage that never graduated. Those who did not go to college would be essentially subsidizing those that did.

The legal challenge to Biden’s debt relief program is now before the US Supreme Court with a decision due around June.

While there is a need for debt relief, it appears the optics of providing blanket debt relief so desired by much of the Democratic base trumped a more strategic approach. The proposal also negatively plays into a narrative touted by many moderates and conservatives of a free spending liberal Biden administration without regard to the growing national debt.

While waiting for a decision by an extremely conservative Supreme Court that champions archaic notions of state’s rights and that will likely overturn decades of precedent that allows universities to harness a measured approach to affirmative action, the Biden administration is also formulating an overhaul of the department’s income-driven federal loan repayment program. In an announcement recently, undergraduate barrowers would have a cap in their repayment set at 5 percent of their discretionary income; graduate student borrowers’ payments would be capped at 10 percent for their discretionary income.

Scroll to Continue

The Story of Blue and Red States

In the most-simple terms, there is a red and blue state divide over the role and importance of public institutions, including universities. There is also a handful of so-called purple states: states in which no one party has a significant majority of votes and that, for instance, might have a Democratic governor and a Republican majority in the state legislature.

While Democrats picked up two additional governorships in the mid-term elections, it did not substantially change the power dynamics between and among the states: Republicans hold 28 out of 50 governorships and retain majorities in a similar number of state legislatures.

The vast majority of red states are rural and more homogenous in population with conservative values focused on limited government and low taxes; blue states, and the Democratic party, are characterized by the concentration of their population in more liberal and diverse urban centers and increasingly liberal suburban populations. Blue states tend to have higher educational attainment rates, including those with a bachelor’s degree. With some exceptions, they are also the hubs for technology and other growth economic sectors.

Most blue states, and their lawmakers, have a general sense of the value of public universities and colleges, and are seeking paths to re-invest in them after the severe ebb of state funding before and during the Great Recession and the onset of the COVID pandemic. In contrast, a Pew Research Center survey found that some 59% of Republicans feel that colleges and universities have a negative effect on American society.

Red state politicians see advantage in attacking universities as reinforcing the “deep state,” and focusing on cultural issues revolving around race and gender fluidity debates. To varying degrees, the Republican lawmakers have embraced many of the characteristics of right-wing neo-nationalism found in other parts of the world: anti-immigrant, nativist and isolationists, prone to anti-science rhetoric and policies, seeking ways to gerrymander and control elections, and finding subtle and sometimes overt ways to attack political opponents and to gain greater control of public institutions, including universities and the judiciary.

At the same time, funding has generally improved for higher education in both red and blue states, in part because of the federal government’s massive infusion of pandemic relief funding directed to state governments and a generally improving economy, despite high inflation rates. Blue and red, and purple, state politics also finds consensus on the important role of tertiary institutions in workforce development and regional economic development.

Attacks on Higher Education

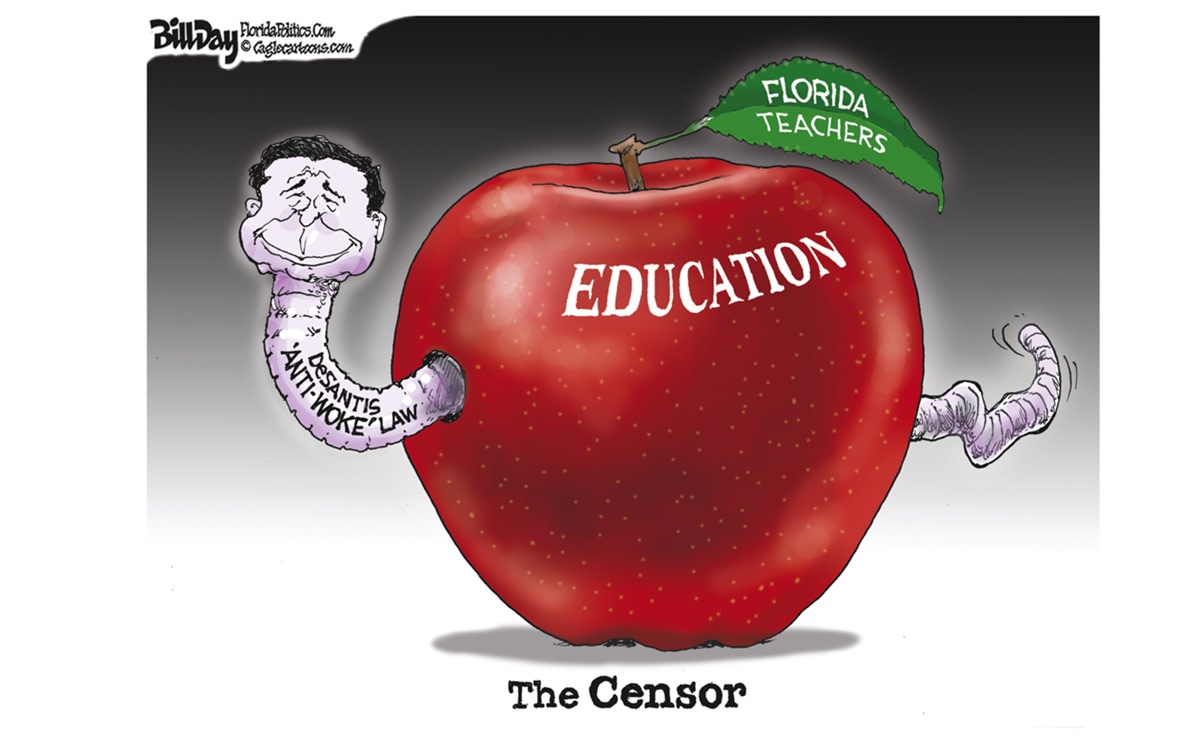

Governors in many red states have sought paths to populate public university governing boards and university presidencies with conservative loyalists. In Florida, for example, Republican governor Ron DeSantis, a presidential hopeful who now exceeds Trump in popularity among Republicans in recent polls, has repeatedly targeted universities, and schools in general, as proponents of critical race theory (CRT) and dogmatic enablers of LBGQT rights.

In part based on a national legislative template offered by an activist conservative lobbying group, the Florida legislature passed a bill last May banning the teaching of CRT and restructuring tenure; another law allows students to record professors’ lectures as evidence of possible bias.

Apparent fear of political and funding retribution led the president of the University of Florida, its flagship state university, to initially ban faculty from testifying against a DeSantis backed effort to pass legislation widely believed to limit voting rights of minority groups who more generally vote Democratic. DeSantis also recently appointed a Republican Senator from Nebraska, Ben Sasse, as president of the University of Florida (UF) despite significant protests from faculty. It’s an odd fit.

Florida has become an important battle ground regarding issues of academic freedom and university autonomy, but similar legislation has been passed or introduced in Oklahoma, Mississippi, North Dakota, Texas and other states.

In Texas, the Lieutenant Governor voiced a common critique among conservatives regarding the flagship University of Texas campus in Austin: “Tenured professors must not be able to hide behind the phrase ‘academic freedom’, and then proceed to poison the minds of our next generation . . . “

In Georgia, and despite widespread faculty protest, Republican governor Brian Kemp appointed former two-term governor Sonny Perdue to lead the 26-institution University of Georgia system; its governing board then made it easier to fire tenured professors.

Seeing into the Future

As we move into 2023, there are some signs of a more moderate political environment in the US, but also a moderating and possible mild recession economy, and probable gridlock in any meaningful policymaking at the federal level with the Republican’s gaining their slim majority in the House of Representatives.

The ascending Republican leadership in the House remains fixated on retaining the old Trump political base and blocking any new initiatives from the Biden administration – whatever their merits.

Trump’s errant higher education policies, including yearly proposed massive cuts in federal funding for academic research, were largely averted by a consensus of both parties in Congress. The largest residue from the Trump period of chaotic policymaking is the rhetorical attacks on higher education and the broader effort to cast science and scientists as tools of a vast liberal conspiracy of disinformation.

With Trump’s increased political and legal baggage, I think it unlikely for him, and his scorched earth policies, to return to the presidency. Without a clear agenda, or leader, and disarray in the Republican party, much of Biden’s agenda for higher education is in place and will shape the year ahead.

This includes the recent $1.7 budget deal passed in late December and signed by Biden that includes a moderate but meaningful increase in funding to the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Further bolstering federal funding for higher education, the recent CHIPS and Science Act will bolster US microchip research and production and will funnel additional funding to academic researchers — further building generally positive collaborations between universities and the private high-tech sector that has fueled economic growth.

These bi-partisan deals also allowed the federal government to operate into early 2023. But there is uncertainty about the future of the federal budget that in a worse case scenario could mean cuts to mandated programs like social security and discretionary funding, like to the NSF and the NIH.

Republicans have repeatedly used the arcane requirement for Congress to increase the federal debt level, threatening to close down the government and sowing political favor from the party’s obstructionist base. As of this writing, they are doing this again, calling for more than $130 billion in unidentified cuts to the federal budget. Brinkmanship aside, one assumes that a deal will be made in the next five months or so and the US will meet its debt obligations.

The economic fortunes of the US, and globally, will also play a role in shaping domestic policy, along with the pending decisions by the Supreme Court on Biden’s debt relief scheme and the probable decision to end America’s brand of affirmative action at universities – although the use of race and ethnic preferences in university and college admissions is in reality practiced by only highly selective institutions that enroll only about 6% of all students.

As we move into the presidential race period, the red versus blue state dynamic, with political debates and news coverage often revolving around cultural issues that play well among Republican and many independent voters, will likely become even more heated. These are so-called “wedge” issues that drive tribal political actors and voters.

While much of this discussion is on domestic policy, there remains the important question of the path forward for the international engagement of higher education institutions in the US, including international research collaborations between universities and between scholars and students.

Putin’s savage attack on Ukraine, increased tension with China regarding not only trade but science and technological espionage, has created what might be termed a new and emerging academic cold war.

How the US, and the world, navigates this relatively new environment, and its influence on what has become an extremely robust global science system, is not clear. On the one hand, it is leading to increased isolation for universities and academics in parts of the world, particularly Russia but also in an increasingly autocratic China. On the other hand, it may lead to an even more robust relationship with the EU and possibly key portions of the southern hemisphere.

In the end, and as this short synopsis of contemporary higher education policy and politics in the US shows, elections matter – at least in liberal democracies.

Source link