Malachi “Kai” Haswell couldn’t quite believe what she was reading in the public court filings.

The attorney was part of a team at Bay Area Legal Aid investigating seemingly interconnected junk debt companies for allegedly submitting false proofs of service, or telling courts that they’d notified defendants of collections lawsuits against them when they hadn’t.

In paperwork filed by Achievable Solutions Inc., a Southern California company that purchases uncollected debts from creditors and tries to collect, ASI claimed it provided “proof of service,” or in-person notices, to California consumers who had failed to pay their debts. Studying ASI’s paperwork, Haswell didn’t know how those claims could be true.

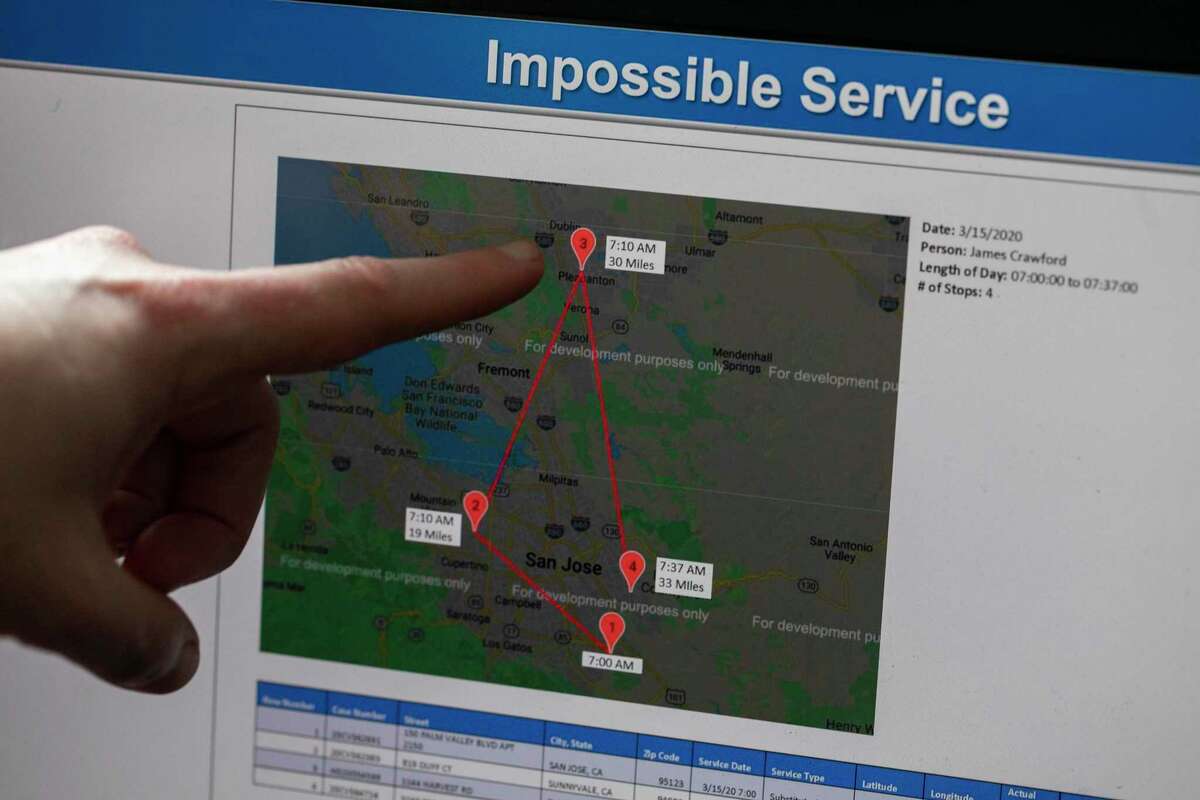

On Jan. 25, 2020, for example, a “James Crawford” was supposed to have traveled 49 miles from Milpitas to San Francisco in five minutes, then 32 miles to Hayward in 20 minutes, and then 30 miles to San Jose in three minutes, all while serving residents with notices of lawsuits, according to the court records.

“Anyone living in the Bay Area knows this is an implausible task to do,” said Haswell, who now works at Kemnitzer, Barron & Krieg, a Mill Valley law firm. “It is quite clear that ASI failed to properly serve people with notices as required by California law.”

In March 2022, the nonprofit Bay Area Legal Aid, Haswell’s employer, and Walnut Creek law firm Bramson, Plutzik, Mahler & Birkhaeuser, sued ASI in Alameda Superior Court alleging a “litany of debt collection abuses against hundreds, if not thousands, of California consumers.” The civil lawsuit, which does not represent any individual consumer and is not seeking financial damages outside of reimbursed legal fees, aims for a permanent stoppage to ASI’s operations and connected businesses.

Attorney Kai Haswell points to a map showing how quickly a process server allegedly crisscrossed the Bay Area on a single day to serve people with lawsuit notices. Haswell believes the server is a fiction and that the lawsuits were never delivered.

Salgu Wissmath / The ChronicleThe lawsuit further alleges that the company files debt collection cases against consumers and then “deliberately fails to serve them with notice of the case” so that the consumers fail to appear in court and default judgments are entered against them. There is a term for such a practice — sewer service — and it denies consumers an opportunity to defend themselves.

Collections lawsuits like these, even for small amounts, can have a detrimental impact on consumers, many of whom are low-income, Haswell said.

“People’s lives are ruined,” Haswell said. “They can lose everything in a moment.”

According to Debt Collection Lab, a tracker started by Princeton University, nearly 71 million U.S. adults had a debt turned over to a private collection agency in 2018. Less than 10% of debtors had legal representation. Many people do not respond to the lawsuits. A 2020 Pew study found that default judgments, where a judge rules in favor of a creditor, are alarmingly common, as high as 70% of all debt cases.

There are numerous reasons why consumers do not respond, said Whitney Barkley-Denney, the deputy director of state policy at the Center for Responsible Lending, a nonprofit policy firm in Durham, N.C.

“Some people don’t show up because they don’t ever get notified,” she said. “But even if you do get the proper paperwork, it’s an intimidating process to go through.”

Unlike criminal cases, defendants in civil cases do not have a constitutional right to an attorney.

“So they’re going to have to show up and represent themselves. They may not know how the process works, so they may just decide not to show up at all,” Barkley-Denney said. “That also leads to an enormous number of cases defaulting — unfortunately too many judges are quick to rubber stamp these default judgments.”

For consumers, that can lead to things such as wage garnishment or court liens on homes, draining money for rent, food and gas, and creating a domino effect of dire financial consequences.

Practices like these deepen inequities and exacerbate the nation’s racial wealth gap, Barkley-Denney said. In California, 15% of white communities have debt in collections compared to 25% of communities of color, according to the Urban Institute’s interactive debt map.

Bay Area Legal Aid was first alerted to ASI’s alleged practices when a local resident, John Chambers, came to their legal clinic in February 2021, after learning by mail that a default judgment had been entered against him. Chambers, who declined to be interviewed, said he was never served with a summons, according to the lawsuit.

The description of Chambers filed by ASI’s proof of service lists him as a Hispanic male in his 40s with black hair and brown eyes. Chambers is white with blue eyes and dark brown hair, and is in his mid-50s. Bay Area Legal Aid got the judgment against Chambers dismissed after pointing out the factual errors.

The lawsuit alleges that the proofs of service filed by ASI are fraudulent and that the person said to be serving them, James Crawford, is most likely fictional.

ASI Inc. is owned by defendant Takashi Cheng, who also operated A-United Services, a process-serving company purchased in 2018 by Pasadena-based Sue Ya Inc. The online platform, which Cheng also owns, advertises that it makes suing “easy” on its website. Woodland Hills law firm, the Harris Law Group, was the entity representing ASI in the legal actions against consumers, according to Bay Area Legal Aid. Kiona Tchan, a financial officer for ASI, is also named in the lawsuit. None of the companies returned The Chronicle’s request for comments.

They’re trying to get the lawsuit against them dismissed.

Attorney Kai Haswell says she was inspired to go into law after a former boyfriend became the victim of a fraudulent debt collection lawsuit. Photographed at her home in Oakland, Calif., on Monday, Jan. 9, 2023.

Salgu Wissmath / The ChronicleIn court filings, ASI and its co-defendants contend that Bay Area Legal Aid doesn’t have standing to bring the lawsuit because the law firm didn’t suffer any harm. Bay Area Legal Aid intends to present evidence next week that the defendants’ alleged activities forced it to spend countless hours of staff time investigating and attempting to mitigate the effects of those practices.

Bay Area Legal Aid said it doesn’t have unlimited resources and this kind of intensive work severely limits its ability to fulfill its mission of providing legal representation to low-income people in the Bay Area.

“We believe that the current dispute is a red herring, trying to distract the court from the rampant fraud the defendants have perpetrated on California courts and consumers,” Haswell said. “We hope to present our evidence of the defendants’ practices and make sure they are permanently stopped.”

The number of civil lawsuits have declined during the pandemic. In the 2020-2021 fiscal year, California’s superior courts saw 62,076 small claims lawsuits seeking amounts under $10,000, more than a third of which — 22,295 lawsuits — originated in Los Angeles County, where ASI is based.

Less than a percent of small claims lawsuits get dismissed, though it’s unclear how many result in judgments for the plaintiffs. In the Bay Area’s four largest counties — Alameda, Contra Costa, San Francisco and Santa Clara — only Contra Costa Superior Court dismissed any small claims lawsuits in the 2020-2021 fiscal year, according to the Judicial Branch of California.

For Haswell, the lawsuit hits close to home. In 2011, when she was a grad school student at Colorado State University, her then-boyfriend’s credit card debt was acquired by a junk debtor. Court documents claimed the boyfriend was served with notice of a collections lawsuit, but no one ever came to their home to notify them or to serve them paperwork, Haswell said.

“The circus around trying to find out information and scraping money to fight this legal battle was one of the most stressful times of our lives,” Haswell recalled.

The experience changed the course of her career. At the time, she was pursuing a master’s degree in philosophy and was considering going for her Ph.D. Instead she was inspired to become an attorney.

“I think about how scared we were — and this is two educated people engulfed in this,” she said. “I can’t imagine what it’s like for people who may be undocumented, have language barriers, or just don’t know where to turn.”

Shwanika Narayan is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: shwanika.narayan@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @shwanika

Source link