U. J. Alexander/iStock via Getty Images

I was in Stockholm, Sweden, on Tuesday January 10 and read US Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell’s presentation at a Riksbank (Sweden’s Central Bank, the world’s oldest as it was founded in 1668) symposium on central bank independence. This was Chairman Powell’s speech:

Speech by Chair Powell on central bank independence

Of all things in the world, there is little with which to disagree about Chairman Powell’s remarks, for as far as they go. He said that a central bank, such as the US Federal Reserve, needs to be independent in order to take decisions that may be politically unpopular in the short term.

There is an important limit to Chairman Powell’s remarks, however: The difficulty of the nature of the task. Yes, the Fed should be independent so that it can take politically unpopular decisions. The problem is that this says nothing about the options available given the nature of the circumstance: Yes, the Fed can take unpopular decisions, but will it, under political and public pressure?

Being brave doesn’t say much about the outcome when faced with an impossible situation. If you are facing a flock of hungry lions or you’re on an airplane where the wing just fell off, it may not matter if you are “independent” or “brave” — because you are about to meet your maker no matter what you may be willing to do in order to attempt to rescue the situation.

As usual, they say it’s difficult to predict the macroeconomic outcome

Macroeconomic predictions are normally difficult and uncertain. There are many variables, and the outcomes could swing in multiple ways. From 1987 to 2020, there was always some “escape hatch” that the Fed could pull, in order to avoid a total economic meltdown. In plain English, that meant cutting interest rates and/or engaging in some form of quantitative easing, aka “money-printing.”. And guess what? 1987 is about as far back as almost all of today’s active Wall Street careers go. Almost everyone working on Wall Street today knows nothing about investing in anything that works beyond falling interest rates and rapid expansion of the quantity of money.

However, the main issue that is now confronting the U.S. — and some other countries — is in my opinion unusually easy to predict, as we enter 2023. The forces at play are so harsh and radical that I estimate that not even a miracle could prevent the greatest financial crisis in a century from unfolding already within the next year or two.

This time it’s easier: The inescapable math appears devastating

All you need to know in order see where things are going on the macroeconomic front is to combine a four hard cold facts about our macroeconomic circumstance:

-

US Federal issued debt to GDP is 125% and rising fast.

-

US Federal real cash budget deficit is at a record level and rising fast.

-

Interest rates on the US debt are growing from around 1% a year ago to a projected 5% in the coming year.

-

The US Federal Reserve goes from $120 billion per month in Quantitative Easing (QE) to $95 billion per month in Quantitative Tightening (QT). That is a $215 billion per month swing, draining market liquidity.

Any one of these four facts could potentially be survivable by a nation, in isolation from the other negative circumstances. Combine that one negative factor among the four above with favorable conditions among the three other factors, and you might “only” have a recession, even if it’s a deep one.

The problem with 2023 is that all four of these storms are now hitting the target simultaneously. It is a perfect storm: A once-in-300 years Category 7 twister. Nobody alive today has seen anything like it happening in the US markets in their lifetime.

Let’s take the four components of the “Category 7” perfect financial storm in turn, and comment on how any one of them could be survivable (but isn’t!):

-

You could deal with the record debt if the economy was booming (GDP growth), the deficit was zero or negative, and interest rates were falling. But the opposite is happening.

-

You could deal with a rapidly growing budget deficit (for a while) if it came on the backs of having no debt (or being a creditor) so that you could “invest” for a while, plus pay it off with superior economic growth and a high/rising level of personal savings. But the opposite is happening.

-

You could deal with sharply increasing interest rates if the debt level was low and falling, and if the budget deficit was also low and falling. But the opposite is happening.

-

You could deal with going from huge QE to huge QT if all the three factors above were going in the opposite direction. But the opposite is happening.

In short, every single factor that could be tilting over the US fiscal ship into the wrong direction, is happening. It’s a “four out of four” in terms of deadly macroeconomic blows: Heart attack, stroke, stage four cancer and poisonous snake bite — all at once.

In an airplane analogy, the wing fell off, one engine is on fire, the other engine is dead, the jet fuel tank ruptured, and the pilots both had simultaneous heart attacks. This plane is crashing with zero probability of even the slightest hope of survival for anyone on board. It’s over.

The macroeconomic equation hits immovable object at full speed

In case the impossibility of this situation isn’t clear to you, let me spell it out: The US has financed the Federal deficit to a large extent with the US Federal Reserve buying US Treasuries.

Now, the US Federal Reserve says it isn’t going to be buying those treasuries anymore. Adding insult to injury, it is going to unload competing treasuries from its nearly $9 trillion balance sheet. Whatever interest rate the US Federal government was going to pay when it wasn’t competing with The Federal Reserve, it may have to be dramatically higher given that its big buyer isn’t buying anymore. Worse yet, the Fed is outright selling. That’s catastrophe squared for the US Treasury, as interest rates will likely have to increase sharply in order to attract new buyers. This is not some sort of controversial theory, but rather simple bond math: Much lower demand in the face of much higher supply, means higher interest rates. This is the textbook case for a sharp increase in interest rates.

But wait, there is more! Maybe this would work if the US Federal deficit was low and falling. If so, having to sell more bonds to non-Fed sources wouldn’t matter much, if at all. The problem here is that the US Federal budget deficit is now the highest ever, and rising fast. The US Treasury has indicated annualized borrowing needs of $2.6 trillion as the current deficit rate. That’s almost 10% of estimated GDP for the next year, or nearly double where it was only last year.

Actually, there is even more! All of those things might be mitigated by sharply falling interest rates. The problem here is that interest rates are going up, not down. The US government borrowed increasingly short-term in the last decade, and is now going to see a multiplication of the interest rates it is paying, over the next few short years, as the old debts roll over from 1% to 5%.

In short: Everything that could possibly go wrong for the US fiscal position, is going in the wrong direction — and hard, and rapidly. If the Fed continues to do what it says it will do — staying “unpolitical” as described in Chairman Powell’s speech here in Stockholm earlier this week — then the US fiscal position could turn into the largest sovereign financial collapse in over a century. As I will show below, it really doesn’t matter what the Fed does at this point, as the end result looks to be the same in terms of long-term interest rates and an associated economic collapse.

We can compare the disastrous macroeconomic situation in the US with here in Sweden (where Chairman Powell presented this week) and Turkey (which is often used as an example — not by me! — of what should not be copied):

| 2022-23 vital stats | USA | Sweden | Turkey |

| Central gov’t issued debt to GDP | 125.% | 33.% | 44.% |

| Central gov’t budget deficit to GDP | 6.% | 0.% | 6.% |

| annual GDP growth | 1.% | 2.% | 3.% |

Data Source: Statista

Three points emerge from the table above:

-

Issued debt by the central government: The US has by far the most amount of debt in relation to its GDP, approximately 3x Turkey and 4x Sweden.

-

Central government deficit in relation to its GDP: The US is as bad as Turkey, and dramatically worse than Sweden.

-

Economic growth: US economic growth is half as fast as Sweden, and one-third that of Turkey’s relatively fast-growing economy.

Let’s see: The US has the most debt, the highest deficit, and the slowest economic growth. In this precarious situation, US interest rates are skyrocketing and the US Fed is not only going to stop buying US treasuries, but also start to unload its balance sheet of the Treasuries that it already purchased over the last decade. All of that in a rising interest environment. What could possibly go wrong? Answer: Everything looks to be guaranteed to go wrong.

The Fed pivot: I dare you

The reason that the market has not tanked more in recent months, with these prospects, is that the broad market consensus has a solution to this sovereign debt crisis/problem: The Fed is going to “pivot” — cut interest rates, and more importantly stop selling Treasuries in favor of once again buying them in great quantities, such as well over $100 billion per month, instead of selling a similar amount. Remember, at $2.6 trillion per year worth of a deficit, the Fed is likely going to have to buy approximately $200 billion of treasuries per month, in order to finance the US Federal budget deficit.

Why may such a Fed pivot not work this time? I submit that a critical factor has changed this time, compared to anything that US market participants have known ever since the 1987 October Black Monday crash. Over the last 35 years, the US did not have much inflation from 1987 until 2021.

This time around, however, the Fed has staked its reputation on getting inflation down to 2% or below, staying below 2% for a while to balance out the runaway numbers we saw in 2021-22, and still in 2023. What would be the macroeconomic reaction to the Fed abandoning its promise to fight inflation?

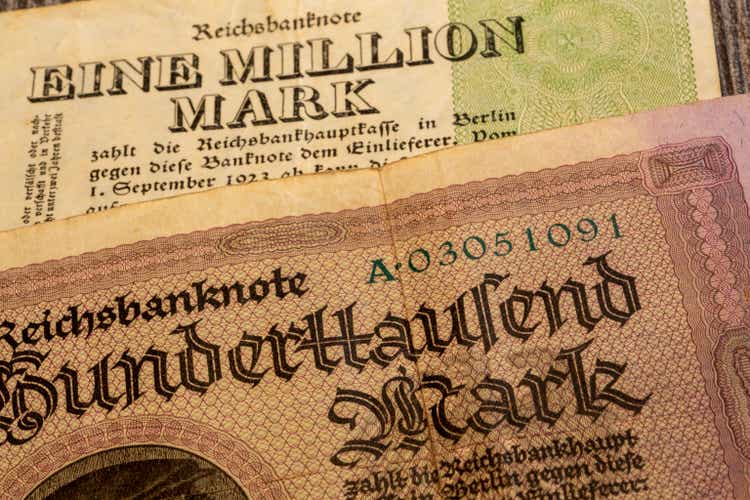

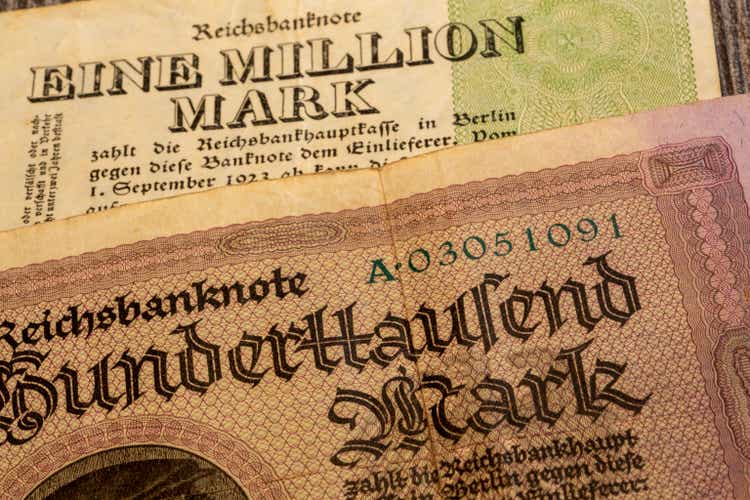

The answer is that the US would likely be back to a far more aggressive repeat of what happened in the decade following the August 15, 1971, abandonment of the last remnant of the gold standard. Gold jumped from $35 per ounce to $850, the dollar fell, interest rates spiked up to the teens, and the economy suffered under stagflation. Those were bad years, economically, and they did not end until Fed Chair Volcker cleaned up with the induced 1981-82 deep recession.

This time, however, the problem is that US Federal debt as a percentage of GDP is no longer 30%. Rather, it’s 125% and rising fast. The US budget deficit is out of control at $2.6 trillion per year. In 1961, President JFK signed the first US Federal budget where all Federal spending combined was $100 billion — one twenty-sixth of the deficit rate exiting 2022!

In addition, unlike 1971-1980, this is happening at a time when US interest rates are already near record-low by historical comparisons. Basically, even if it were possible to cut the current rates, the Fed couldn’t cut by much. Worse yet, even that limitation pales in comparison with the $9 trillion Fed balance sheet: Back in 1971, the Fed balance sheet rounded to zero. It is like comparing a current Olympian athlete to one of those television horror stories of a patient who weighs 800 lbs and can barely walk to the bathroom. The 2023 US Federal patient is no current Olympian athlete, but rather one heartbeat away from sudden fiscal death, not someone who can be rustled out of his sick bed and start jogging.

A Fed pivot could mean a fatal loss of sovereign/currency confidence

The US monetary-fiscal regime is already skating on thin ice. Even if nothing else happened, the 125% debt in combination with the $2.6 trillion deficit and rising interest rates could lead to the same kind of sovereign debt crisis that happens in every country that faces those kinds of numbers. Paying 5% on $32 trillion in debt is over $1.5 trillion a year, and at that rate within half a decade that would swallow nearly 100% of US Federal tax revenue. There is no nation in world history that has managed to withstand anything like that, and avoided a currency collapse.

In this context, if the US Fed were to “pivot” then the little remaining market confidence in the US Fed would go out the window immediately. The US dollar could collapse and the US long-term interest rates could skyrocket.

The US Fed could lose control of long-term interest rates

Some market participants may think — clearly do think — that interest rates are under the Fed’s control, sort of like pushing a button and magically obtain a result. If this were true, then no country on Earth would ever have to fear high interest rates: The central bank would simply “deem” them so. Every country could borrow in its own currency at a magic near-zero interest rate. There could never be any sovereign debt crisis. Why didn’t anyone think of that before?

If the Fed surrenders its purported fight against inflation by reversing 180 degrees from QT to QE, the collapse in the US dollar could see a simultaneous rise in long-term US interest rates. The US economy is already in the process of buckling under the prospect of reaching 5% interest rates by the second quarter of 2023, seeing as GDP growth is 1% or lower, flirting with negative growth in two quarters during 2022 alone. The US clearly cannot survive higher rates without slipping into recession.

Both metrics — US government debt and deficit — are now dramatically worse than they were in the 1970s. As a result, the pain to deal with this via higher interest rates, would be much worse now than it was 40-50 years ago. It therefore appears logical that interest rates must therefore peak much higher than the 13%-17% rates we saw around 1981.

The US Fed therefore has a simple choice:

-

Voluntarily increase rates to at least in the ballpark of 20% as a pre-emptive measure to bring inflation down under 2% on a sustained basis. Such sharply higher rates would obviously crash asset prices. Whatever stocks you own, as well as real estate, in such a scenario you should probably sell them or outright short them.

-

Pivot and hope to solve the situation by returning to quantitative easing. As a result of a loss in credibility and confidence, this could crash the US dollar and cause the private market to push long-term interest rates to somewhere around 20% “involuntarily.” I mean, who lends money to countries in Argentina and many other countries at less than 20%? Remember, Turkey and Sweden have better macroeconomic stats than the US, per the table above. So do many other countries. The US interest rates would have to reflect the 125% debt to GDP ratio, and the record budget deficit, both of whom are way worse than Turkey’s numbers.

Much higher interest rates ahead: By hook or by crook

It therefore follows that the US is about to face dramatically higher interest rates, one way or the other. They will either happen “voluntarily” or as a result of a US sovereign debt collapse, which also would mean a US dollar currency collapse. Can you spell $15 per gallon gasoline?

Market outlook: Prepare for the potential for 20% interest rates

As a result of the logic outlined above, record-high interest rates are coming, whether as a result of voluntary Fed actions to fight inflation, or as a result of a US sovereign debt collapse happening first. Either way, interest rates will logically rise higher than where they peaked in 1981, because the problems that face the US now (US government debt and deficits) are that much worse by every metric. There is no exact way to predict where this will end/peak, but if the 1981 rates were around the mid-teens, this time it must logically be meaningfully higher. That’s why I estimate 20%, but that’s clearly not the ceiling. If the market consensus becomes that the US dollar will depreciate by 25% per year, interest rates would need to be at 33% just to “keep even” with the dollar depreciation. And that’s before a risk premium! We could be looking at nearly 50% interest rates in such a scenario. In my opinion, in such a loss of confidence in US treasuries and the US dollar, the US government could default almost immediately.

Asset class outlook: Short everything except gold

Stocks, bonds and real estate could possibly get crushed under such a coming interest rate normalization. I don’t think that needs to be explained! The more important question is where to hide in such a scenario.

My bet in that regard is gold (GLD). In a currency collapse, a sovereign debt collapse, investors may yet again flock to an unleveraged asset without traditional counterparty risk. From 1971 to 1980, gold saw radical appreciation as US bond prices, real estate and stocks were re-rated based on higher interest rates and inflation. From 1971 to 1980, the gold price increased by approximately 23 times at the peak! (from $35 to $850).

Counterpoint: Please rebut my thesis

I have presented one of the grimmest macroeconomic outlooks imaginable. It is based on the consequences of the record US Federal debt (125% of GDP and rising fast), the record budget deficit (which is also rising fast) and that interest rates are going up, not down. I have also shown that if the Fed pivots, the market is likely going to punish the US dollar and thereby cause long-term US interest rates to skyrocket, perhaps to 20% or more.

If you have an alternative thesis as to how the US gets out of this debt spiral, without seeing long-term interest rates skyrocket and the US dollar collapsing, please present it.

As it stands, my thesis presented above is that the US macroeconomic vessel is about to hit the immovable object of a hard rock reality at full speed. The crash would not be a pretty sight for many or most market participants, including civilians such as homeowners and pension fund savers.

In my opinion, the only (relative) winners may be gold miners (GDX) and especially gold bugs (GLD).

Source link